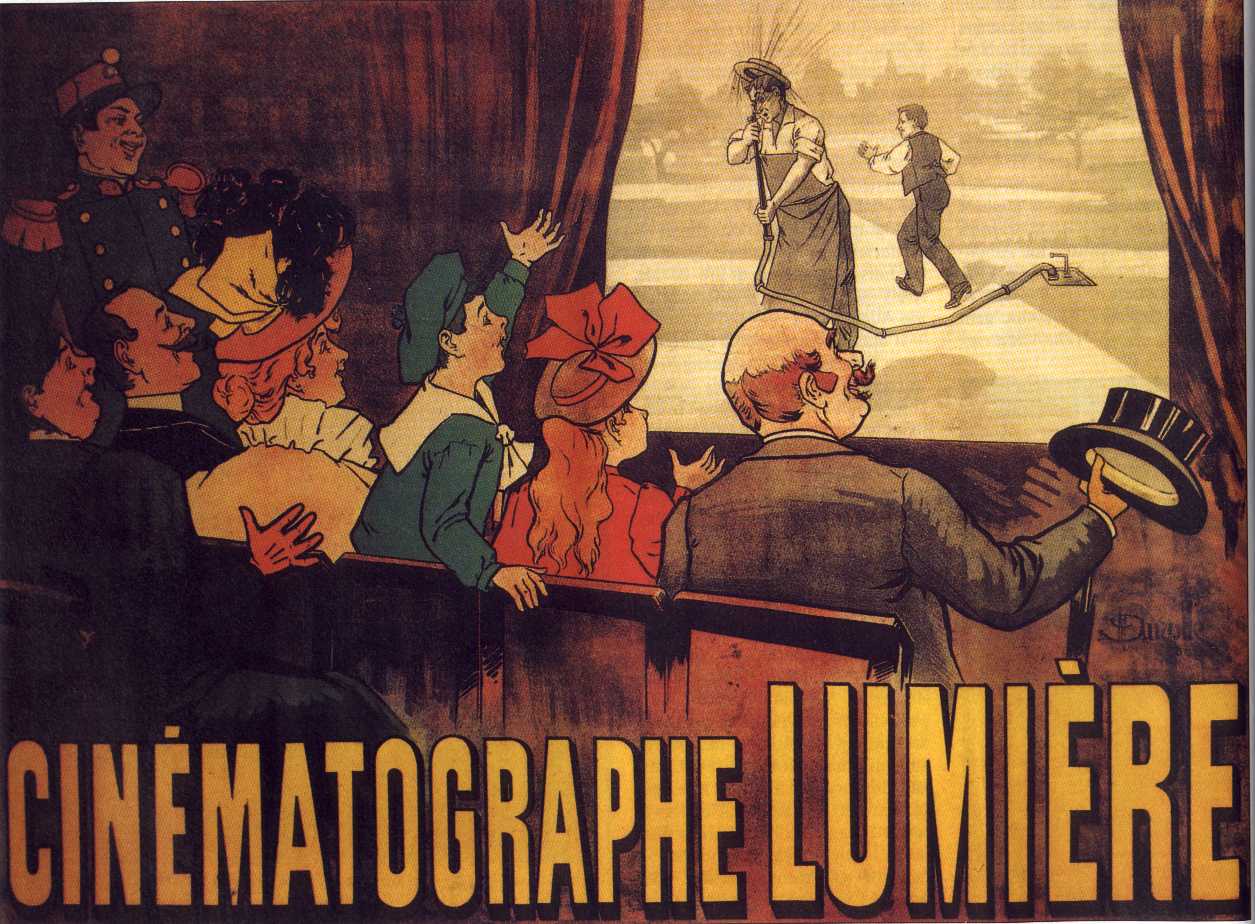

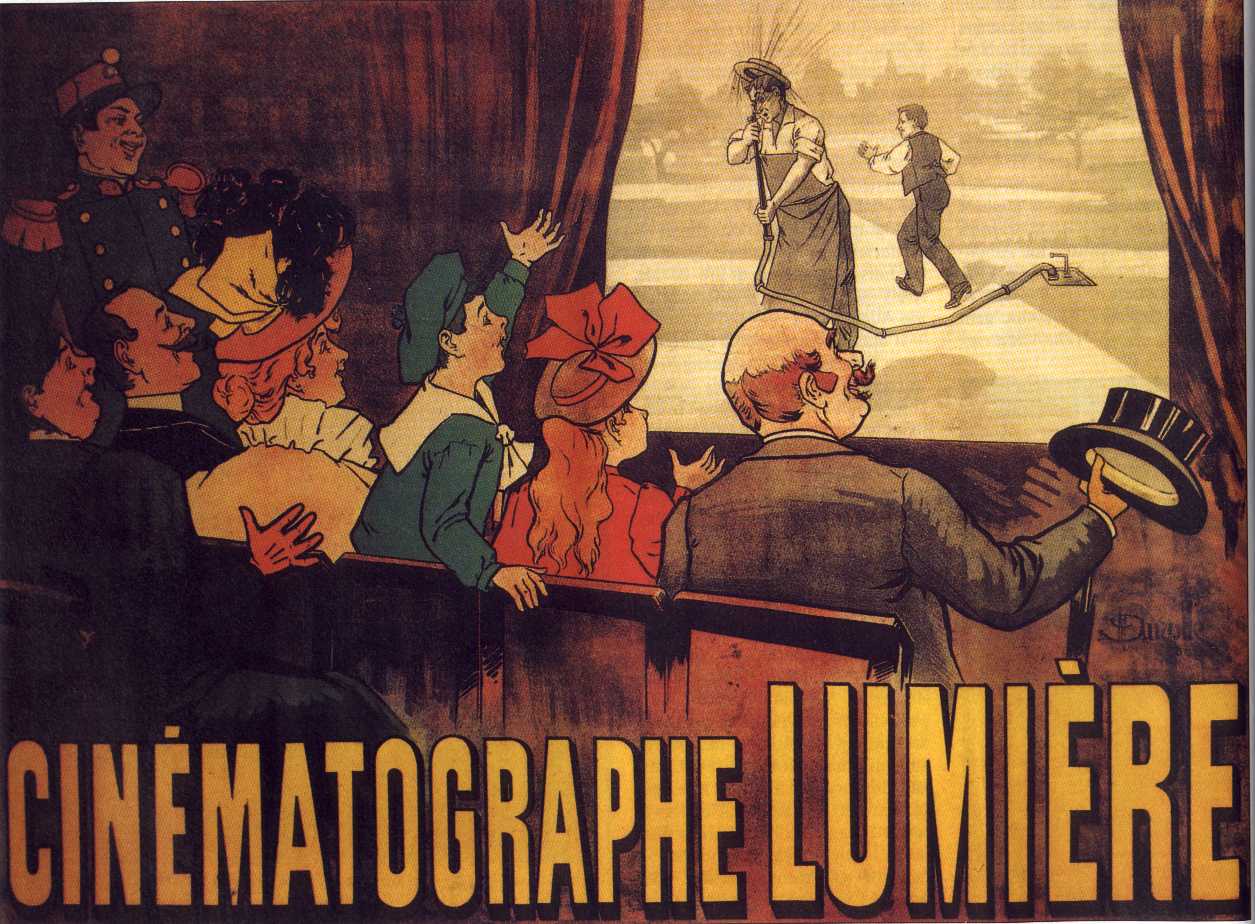

The first movie theatres were rented rooms and music halls. As movies gained popularity and the technology of showing moving images improved, going to the movies was transformed into a magical experience.

The first movie theatres were rented rooms and music halls. As movies gained

popularity and the technology of showing moving images improved, going to the

movies was transformed into a magical experience.

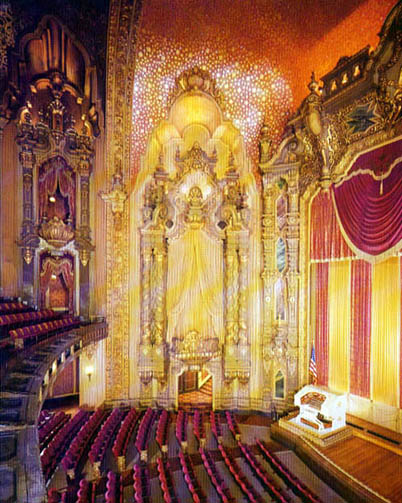

Many of the movie theatres of the 1920s and 1930s were so grand that people nicknamed them "picture palaces." Exteriors were gaudy, electric extravaganzas in the style of art deco, Middle Eastern or Asian architectures.

Inside the palaces, smartly uniformed ushers led moviegoers through luxurious marble-lined halls the size of cathedrals, under crystal chandeliers, and up plushly carpeted stairs to their seats. They offered every convenience, including restaurants, nurseries for children, free telephone calls, art galleries, dance floors, and billiard rooms. While waiting for the film to start, patrons could be entertained by a ballet, orchestral music, the "Mighty Wurlitzer" organ or other stage attractions.

The

aim of grand theatres was to encourage people to see films frequently. The tactic

worked well: In 1930, at the start of the Depression and when the population

of the United States was 122 million, Americans were going to the movies 95

million times each week.

The

aim of grand theatres was to encourage people to see films frequently. The tactic

worked well: In 1930, at the start of the Depression and when the population

of the United States was 122 million, Americans were going to the movies 95

million times each week.

The Uptown Theatre

The Uptown Theatre in Chicago is a representative "picture palace". Built in an elaborate Spanish Renaissance style in 1925, it covered 46,000 square feet and seated 5,000. The lobby held pillars that ascended six stories to a dome ceiling. It employed over 130 people, including two firemen, a nurse, and 34 orchestral musicians.

When was the last time you saw an usher at a theatre? In the large theatres of the 1920s and 1930s, ushers were essential. Not only did they show individual persons to their seats, but they were charged with handling large crowds. During the vaudeville era, three shows a day were the norm. For a 4,000 seat theatre, some 20,000 people were moved in and out of the theatre in a day! This required considerable handling skills since intermissions were often less than one half hour.Ushering at one of the big theatres was a very desirable job. The uniforms were smart and the ushers were entitled to free passes for friends and relatives. In 1926 the Chicago Theatre (4,500 seats) hired a retired West Point colonel to train the ushers!

During the vaudeville era, large movie theatres

employed sizeable numbers of people. The Uptown Theatre in Chicago (4,800 seats)

employed over 130 persons, not including the traveling vaudeville acts.

The men's and women's lounges in the large theatres were quite luxurious. The ladies lounge of one theatre had a screen to allow the ladies to view the picture while in the lounge. This was done with an arrangement of mirrors reflecting images from the projection booth.

Some of the theatres provided supervised playrooms to entertain children while their parents viewed the movie. One enterprising theatre even featured a cocktail lounge for the "husband who was bored with the romantic movie his wife was watching".

During the 1930s, many gimmicks were used to lure people into the theatres.

Ladies night, which featured lower rates for women.

Free dishes: Faithful attendees could accumulate complete household sets. This practice is how depression glassware got its start.

Cheap Saturday afternoon matinees for kids, often with free ice cream.

Raffles for appliances and even automobiles.

Where else could you sit

in the courtyard of a Moorish or Spanish palace under a twilight sky complete

with clouds and stars and watch a first run movie? It didn't matter that the

palace was plaster, the clouds were painted and stars artificial lights. During

the dark days of the depression, visits to the movie theatre were welcome relief

to the hard times of the day.

Towards the end of the 1930s, theatre design

trends moved from palatial themes towards simpler and less costly art deco designs.

During the depression this was a major consideration.

Many excellent artists and artisans were employed by the major theatre architects. An Englishman named Artur Butner was employed by Rapp & Rapp in the late 1920s. He created the plaster decorations for their theaters, including two reliefs built for the lobby of the Palace Theatre in the Bismark hotel in Chicago. The resulting figures were eight feet high. He used his wife as the model.

When the Oriental was commissioned it was intended to be a departure from the Spanish and French renaissance motifs popular at the time. With the Oriental they got it in spades. The theme was middle eastern and was quite bizarre. It was both praised and panned. English artist Arthur Buttner designed much of the plaster work. Rapp & Rapp were the architects.

After being closed for many years, it was saved

from the wrecking ball. The restored Oriental was reopened in 1999 as the Ford

Theatre for the Performing Arts.

To play the Paramount was

the dream of every aspiring vaudeville performer. When you played the Paramount,

you had reached "the top". This theatre, built by Rapp and Rapp, was

the center of New York entertainment in the 1920s.

By the period of the late

1930s, double features had become popular in neighborhood theatres. A grade

"A" feature was always teamed with a grade "B" or second

rate film. This combination is apparent in these three weekly programs published

in 1937 by the Gateway Theatre in Oakland.

Alas, most of the palatial

theatres have been torn down. Competition from television caused the most damage,

and the high maintenance costs incurred to keep aging theatres going finished

the process. A few have survived as churches and stores, while others have been

fortunate and have become performing arts centers. Typical are the Oakland Paramount,

Lowes (Providence, RI), the Chicago and Oriental (Chicago) and the Rialto (Joliet,

IL). Plans are now under way to restore the Uptown Theatre in Chicago.

| Introduction | Technology and Development | Movie Theatres | Movie Pioneers | Early Locations | Home Movies | Personalities | Movie Quote Quiz |

|

This

page last updated:

September 17, 2001

Original content: Copyright © 2000, 2001 Museum of American Heritage |