A hand-sewing needle has its eye at the broad end and travels all the way through the fabric, pulling the thread.

A hand-sewing needle has its eye at the broad end and travels all the way through the fabric, pulling the thread.

Sewing machine basics --- Accessories --- Milestones

A number of people made technological innovations in the sewing machine.

On this page, read about the many improvments to all facets of the sewing

machine, from basics such as the needle and thread to

accessories developed to make this exciting new

machine even more useful.

Sewing machine basics

The needle

A hand-sewing needle has its eye at the broad end and travels all the way through the fabric, pulling the thread.

A hand-sewing needle has its eye at the broad end and travels all the way through the fabric, pulling the thread.

This obviously wouldn't work in a sewing machine. Early in the machine's development, inventors used a variety of needles, including one with an eye at mid-shaft. Several used a hook rather than a needle. However, it was the eye-pointed needle that proved to be ultimately successful.

Above the eye is a groove called a "scarf," which runs nearly the entire length of the needle. When the needle pushes through the fabric, the scarf eases friction and allows the thread to pass through more easily.

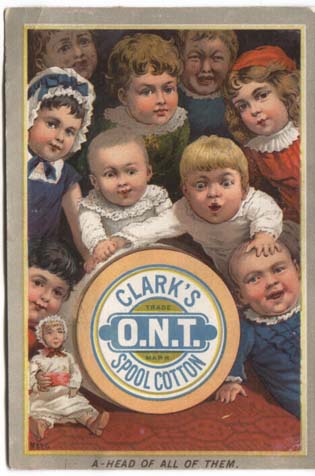

Before the sewing machine, tailors and needle workers stitched with handspun linen thread or handthrown silk. They only used cotton in the form of yarn or floss for embroidery. Around the turn of the 18th century both American and British firms realized that cotton yarn used for weaving cloth could be adapted for hand sewing. Originally customers bought it in hanks. The Clark family in Scotland began winding it on spools for an extra halfpenny -- the customer got the money back when he returned the spool. However, early experimenters with machine sewing found that this three-ply thread wasn't strong enough to withstand the machine's stress.

Before the sewing machine, tailors and needle workers stitched with handspun linen thread or handthrown silk. They only used cotton in the form of yarn or floss for embroidery. Around the turn of the 18th century both American and British firms realized that cotton yarn used for weaving cloth could be adapted for hand sewing. Originally customers bought it in hanks. The Clark family in Scotland began winding it on spools for an extra halfpenny -- the customer got the money back when he returned the spool. However, early experimenters with machine sewing found that this three-ply thread wasn't strong enough to withstand the machine's stress.

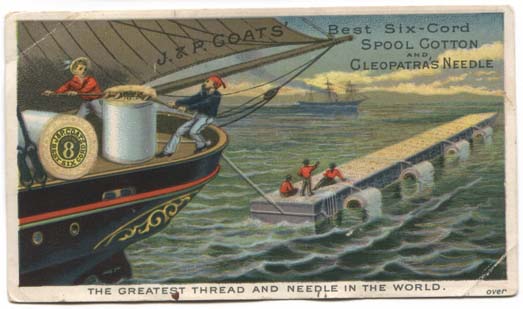

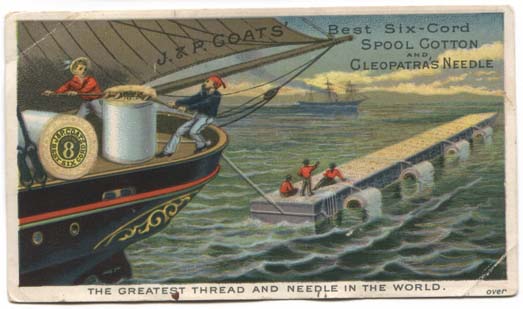

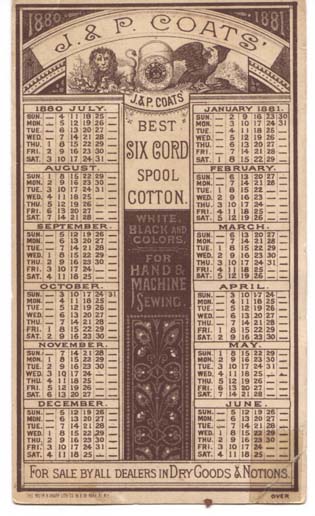

Six-ply thread, developed in the late 1840s, provided more strength from six individual strands twisted together, but still wasn't the perfect solution. In the 1860s the Clark Company came up with an innovation that revolutionized the cotton thread industry. Made in a factory in New Jersey, "Our New Thread" (Clark's O.N.T.) used three sets of two twisted strands. Twisting the three sets together produced a stronger thread that could be used for hand or machine sewing. It was soon adopted by other manufacturers, including the J. and P. Coats Company, which later merged with Clark.

Six-ply thread, developed in the late 1840s, provided more strength from six individual strands twisted together, but still wasn't the perfect solution. In the 1860s the Clark Company came up with an innovation that revolutionized the cotton thread industry. Made in a factory in New Jersey, "Our New Thread" (Clark's O.N.T.) used three sets of two twisted strands. Twisting the three sets together produced a stronger thread that could be used for hand or machine sewing. It was soon adopted by other manufacturers, including the J. and P. Coats Company, which later merged with Clark.

The first sewing machines featured a vertical "basting plate." The tailor or seamstress would fasten the fabric on the plate with pins, and could sew only a few inches at a time before having to re-position the fabric.

To allow for uninterrupted sewing, this basting plate was replaced by a revolving belt, also using pins. Then Allen B. Wilson invented the four-motion feeder.

This device, still used today, is a toothed plate facing upwards against the bottom of the cloth. The cloth, in turn, is held in place by a smooth spring-loaded presser foot (invented by Isaac Singer). The teeth push the cloth forward the length of one stitch. Then the entire feeder plate rolls down, back and up for another stitch. This motion can be reversed to move the fabric the other way, and its travel can be adjusted to change the length of the stitch.

The earliest commercially sold sewing machines used the chain stitch, which requires only a single thread and no bobbin mechanism. While simple to produce, the sewn seam is less stable than one produced using the more modern lock stitch. Nevertheless, the chain stitch is still used in very portable "mini" sewing machines and toy machines. It is also used for crochet and embroidery work.

To produce a chain stitch, the thread which goes through the needle eye is inserted by the needle through the cloth. A "loop hook" catches the thread protruding through the clot, holding the thread as the needle rises. As the cloth advances, the needle descends again, passing the thread through the loop being held open by the hook. The hook then backs and disengages from the first loop, then moves forward to catch the thread again and create the next loop. This prevents the first loop from pulling upward through the cloth, but should the thread subsequently break, there is little but friction to keep the seam from unraveling.

A machine performing lock stitch uses two threads. One feeds off of a reel above the fabric; the other, from a small bobbin below.

The upper, or needle thread, travels through the fabric as in the chain stitch. Here is the important difference. The loop it forms is caught by a hook traveling on a curved path (either oscillating or fully revolving). This hook passes the loop right around the bobbin, thus looping it around the bobbin thread. The needle then withdraws, pulling the intersection of the threads into the fabric.

The upper, or needle thread, travels through the fabric as in the chain stitch. Here is the important difference. The loop it forms is caught by a hook traveling on a curved path (either oscillating or fully revolving). This hook passes the loop right around the bobbin, thus looping it around the bobbin thread. The needle then withdraws, pulling the intersection of the threads into the fabric.

The stitch thus formed looks the same from above and below. Each thread runs across the surface of the fabric and dips into it at intervals to loop around the other thread halfway through the fabric.

Lock stitch is secure and uses a minimum amount of thread, but lock-stitch machines are slower than those performing chain stitch. Moreover, because the needle thread has to pass around the bobbin thread at every stitch, the bobbin has to be relatively small. This makes lock-stitch machines suitable for home use, but not as desirable for industry.

A lock-stitch machine requires a mechanism to inter-weave the needle and bobbin threads.

In early machines a curved needle, threaded at the point, pierced the cloth and then withdrew. When the curved needle was at its apex, the thread was stretched out like a bowstring, leaving a small open space. A shuttle shaped like a little rocket ship or a boat moved through this space, carrying the bobbin thread. As the needle receded back through the cloth, the shuttle returned to its original position.

The smoothest action came from a bobbin mechanism invented by Allen B. Wilson in the early 1850s. Wilson's revolving hook took hold of the loop at its beginning by the eye of the needle and then, instead of putting the bobbin thread through the loop, pulled the loop around the entire bobbin and thread.

A series of tension regulators between the spool of thread and the needles gave slack or pulled taut when necessary, controlling the loop.

This mechanism remains virtually unchanged in modern sewing machines.

Soon after the sewing machine became commercially successful, manufacturers began to look for ways to make their basic machines more versatile. Inventors responded with new gadgets and attachments.

Soon after the sewing machine became commercially successful, manufacturers began to look for ways to make their basic machines more versatile. Inventors responded with new gadgets and attachments.

In 1853, Henry Sweet received a patent for a binder, an attachment used to stitch binding edges to the fabric. Although a machine to make a buttonhole was patented in 1854, and attachments to do this followed, it was not until the late 1860s that a practical one was manufactured.

Other attachments such as a thread cutter, patented in 1857, a bobbin winder, patented in 1857, hemmers, a braid foot and braid carrier, and an embroiderer soon followed. Most early machines used an all-metal presser foot that screwed into place. In 1861 Wheeler and Wilson patented a glass presser foot which enabled the user to see the stitches as they were being formed. Modern sewing machines have transparent clip-on feet.

The popularity of tucked and ruffled garments inspired inventors to provide sewing machine attachments for these purposes. To keep the seamstress cool, C. D. Stewart patented an attachment, driven by the treadle, for fanning the operator. There was also a combined sewing machine and parlor melodeon offered to the consumer. Several 19th century inventors patented an attachment to add an "electric motor."

Most of the basic attachments used today were developed by the 1880s and remain almost unchanged. Even the zigzag machine, popular today, was an outgrowth of the commercial machines of the 1870s.

While machines have become increasingly automated, the basic principles remain the same. One of the most recent developments, a 1933 design, was a machine that imitated hand stitching.

Milliner Ellen Curtis Demorest (1824-98) revolutionized home sewing in the latter half of the 19th century, devising a system of copying fashionable garments onto paper.

In 1860 she introduced Madame Demorest's Mirror of Fashions, featuring the latest styles and a pattern within each magazine. These patterns and the new sewing machines helped democratize dress by placing high style within the reach of the average American woman. She also sold patterns individually, selling more than 3 million patterns in Demorest's best year (1876).

Ironically, she failed to patent the invention. Ebenezer Butterick first published patterns in 1863, received a patent on graded patterns, and built an empire that remains strong in the paper pattern industry to this day.

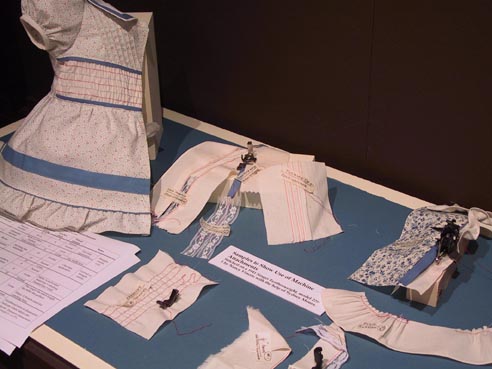

Initially tailors used large sharp scissors to cut cloth to exact size as dictated by the patterns. However, as sewing machines allowed production of larger quantities of clothing, electric cloth cutters began to be developed. Both of these samples were made by the Wolf Electric Co., Cincinnati, Ohio. The cutter with a circular knife (Wolf Type A) was patented in 1888 and cut one thickness of cloth. The Wolf Model 2279 used a thin vertical blade action to cut three thicknesses of cloth. It was extremely important to lay the cloth with selveges exactly aligned so that the pattern could be cut paralleling the threads of fabric. Rollers were provided on the Model 2279 to aid pattern cutting.

Initially tailors used large sharp scissors to cut cloth to exact size as dictated by the patterns. However, as sewing machines allowed production of larger quantities of clothing, electric cloth cutters began to be developed. Both of these samples were made by the Wolf Electric Co., Cincinnati, Ohio. The cutter with a circular knife (Wolf Type A) was patented in 1888 and cut one thickness of cloth. The Wolf Model 2279 used a thin vertical blade action to cut three thicknesses of cloth. It was extremely important to lay the cloth with selveges exactly aligned so that the pattern could be cut paralleling the threads of fabric. Rollers were provided on the Model 2279 to aid pattern cutting.

|

Aside from machine attachments, objects intended to make sewing more efficient or convenient abound. These include thimbles, thread holders, scissors, needle holders, pincushions, sewing boxes and other items too numerous to catalog. Many were (and still are) produced as handicrafts, others incorporated a high degree of skill and artistry in their design and fabrication. Here are a few interesting examples.

Milestones in technical developmentMany inventors worked simultaneously during the first half of the 19th century to produce a workable sewing machine. |

| 1755 | Charles Weisenthal (UK) patented a double-pointed needle having eye at mid-length. |

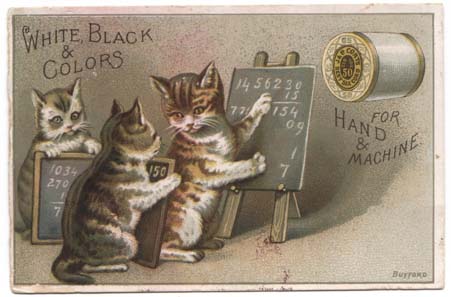

These are postcard sized advertisements for thread that were used in the 1880s. Printed on thin cardstock, they were used as promotional items much the same way as small plastic cards with calenders are used today.  |

| 1790 | Thomas Saint (UK) designed a machine for sewing leather. An awl first made a hole for a hook-shaped needle to pass through (the machine was patented but not built). | |

| 1807 | Edward Chapman (UK) used an eye-pointed needle. | |

| 1810 | B. Krems (Germany) invented an eye-pointed needle. | |

| 1830 | Barthelemy Thimmonier (France) invented the first practical machine, for sewing army uniforms. It produced a chain stitch with a hooked needle, and had a presser foot but no feed mechanism. All 80 of his machines were destroyed by Parisian tailors fearful of losing their jobs. | |

| 1834 | Walter Hunt (USA) invented lock-stitch machines using a curved needle, an eye in the point, and a shuttle carrying a lower thread. The feed had to be constantly reset, allowing only very short, straight seams. | |

| 1842 | John Greenough (USA) received the first U.S. sewing machine patent for his hand-crank machine for sewing leather with a running or back stitch. | |

| 1844 | Fisher & Gibbons (UK) developed the first machine to use the combination of an eye-pointed needle and a shuttle, for decorative stitches only. | |

| 1846 | Elias Howe (USA) invented a lock-stitch machine with a shuttle, curved eye-pointed needle and hand crank. Fabric was held vertically and needed constant re-setting. | |

| 1850 | Allen B. Wilson (USA) invented a double-pointed, reciprocating shuttle (formed a stitch in both directions of the shuttle's movement). | |

| 1851 | Isaac Singer (USA) patented the "Perpendicular Action Sewing Machine," which sewed continuously a straight or curved seam of any length. It was designed for the factory, with a table to support the work horizontally and a yielding vertical presser foot. It was operated by treadle, freeing hands to guide work. | |

| 1852 | Isaac Singer (USA) patented a tension device. | |

| 1853 | Nathaniel Wheeler and Allen Wilson (USA) replaced the shuttle with a rotary hook. The bobbin fitted into the center of an almost circular hook. It was a big improvement and remains remains virtually unchanged in modern sewing machines. | |

| 1853 | William Thomas (UK) patented a free arm, which allowed sleeves and cuffs to be slipped over the narrow work area. | |

| 1854 | Allen Wilson (USA) patented the four-motion feed. |  |

| 1856 | Grover and Baker (USA) patented the first portable sewing machine. It could be cleaned and oiled without being removed from its box. | |

| 1857 | Willcox & Gibbs (USA) patented an inexpensive light-weight machine using single thread and chain stitch. The rotating hook put a twist in each loop, making it more secure than when using a looper. The machine sold for half the price of a Singer or Wheeler & Wilson machine. | |

| 1858 | Isaac Singer (USA) introduced the first domestic lightweight machine: "The Turtle Back." | |

| 1861 | Florence Sewing Machine Co. introduced reverse stitching. | |

| 1865 | Many attachments were available by this time: hemmer, quilter, binder, tuck-maker, friller, gatherer and glass presser foot. Also a thread cutter and bobbin winder. | |

| 1867 | J. H. Cazal (France) introduced an electrically driven machine. | |

| 1872 | Positive take-up was patented. This ensured that the thread was tightened to the same degree for every stitch. | |

| 1873 | Helen Blanchard (USA) patented a zigzag machine. | |

| 1875 | Willcox & Gibbs (USA) introduced an automatic "noiseless" machine with a self-adjusting tension. | |

| 1879 | Isaac Singer (USA) introduced an "Improved Family Machine" with an oscillating shuttle, round bobbin and no gears, making it quieter and speedier. | |

| 1908 | Isaac Singer (USA) designed an oscillating hook machine that had a bobbin sitting horizontally in a holder. This design was used well into the 20th century. | |

| 1921 | Isaac Singer (USA) introduced a portable, electric domestic machine. |

|

This page

last updated: October 4, 2004 Original content: Copyright © 2000 - 2004 Museum of American Heritage Trademarks are the property of their owners |